Features

Making better nutritional choices

Why police officers need to be aware of cortisol and insulin resistance

November 12, 2020 By Derek Thistle

Photo by Mariana Medvedeva

Photo by Mariana Medvedeva How many of us have put on extra pounds since recruit classes? I sure did. I exercised and made “healthy” food choices, yet I often felt tired, irritable, always craved sugar, and put 50 pounds on by year seven. Of course, proper nutrition and sleep are the foundation of health, but if this resonates with you, we also need to look at chronically high cortisol hormone and insulin resistance as contributing factors and better understand how they affect police officers; especially when these issues can lead to obesity, heart disease, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and type 2 diabetes, just to name a few.

Cortisol is the body’s main stress hormone. It’s a “Goldilocks” hormone; we don’t want it too low or too high – we want it just right. It plays a key role in the body’s “fight or flight” response. When we encounter a perceived threat, a high-risk situation or even something like a large barking dog, our adrenal glands release adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones prime our bodies for peak performance, shutting down nonessential body functions, making sugar more readily available for energy. Once the situation is resolved, our cortisol returns to a normal range.

If we look back to our ancestors, this fight or flight response was crucial for survival, whether it was hunting a tiger, fighting a tiger or running away from one! You can appreciate how important cortisol is. The issue though, was our ancestors did not have the constant stressors we have to-day. I am fairly confident early humans in the Paleolithic Era didn’t have shiftwork, job stress, relationship stress, financial stress, investigative call load, public complaints, testifying in court, a grumpy partner, childcare issues, etc. And here’s the kicker: our bodies cannot differentiate between a tiger and these everyday stressors. This results in chronically high levels of cortisol which consistently taps into protein stores via gluconeogenesis in the liver, producing blood glucose (sugar).

Naturally, our cortisol levels are higher in the morning and lower at night. Therefore, we must consider shiftwork and our nutritional choices at night. We have all been there; a busy night shift going call to call (one stressful situation to the next). Our cortisol levels are likely elevated, meaning our blood sugar is as well. We hit a drive-thru, fill up on coffee/energy drinks and eat high glycemic pastries, spiking our blood sugar through the roof. We likely “crash” a little later, feeling tired, irritable, craving sugar and feeling just plain gross.

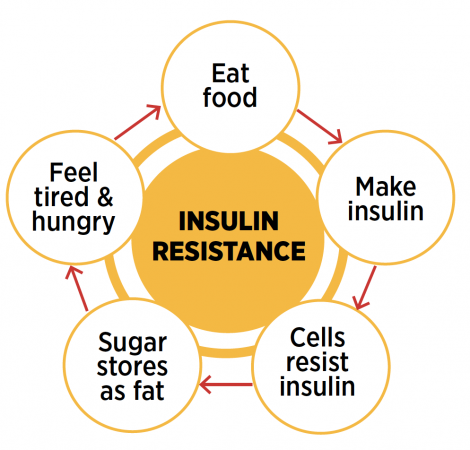

In response to the increased blood sugar, our pancreas secrets the insulin hormone to bring the blood sugar down to normal levels. Insulin is a storage hormone; its job is to open the doorway to the cell, allowing energy (blood sugar) in to be stored. High cortisol means high insulin, and overtime, insulin stops being as effective, and more and more must be released to deal with the excess blood sugar.

“A single night of sleep deprivation can increase insulin resistance up to 33 per cent.”

– Dr. Christiane Northrup

Eventually, the cells simply stop allowing insulin to store all the extra blood sugar. This is called insulin resistance. This condition may be one of the key drivers of many — if not most — of today’s chronic diseases, including prediabetes.

This issue is compounded at night. I think most would agree, a big part of police work is the paperwork and patrol-ling in our vehicles; meaning we are often sedentary. We are likely not using up all that extra blood sugar (for energy needs). To drive this point home for police officers, Dr. Christiane Northrup, M.D., “a leading authority in the field of women’s health and wellness,” stated: “a single night of sleep deprivation can increase insulin resistance up to 33 per cent.”

So, where does all the excess blood glucose go? Your kidneys try and help with frequent urinating, but unfortunately, unless we utilize the blood sugar through energy expenditure, it will get stored as fat. To make it worse, the cells have four times more receptors in the abdominal area, explaining loosening our duty belts and drawing bigger uniform pants every year from the Quartermaster!

The good news is we can keep cortisol levels in check and reverse/prevent insulin resistance. Here are some strategies using nutrition, exercise and supplementation.

Nutrition

The “mission” is to normalize blood sugar levels.

- Eat small meals throughout the day (approximately every three to four hours).

- Meals should consist of lean protein, complex carbohydrates, fibrous carbohydrates (veggies) and essential fats.

- Do not snack in between meals (to allow blood sugar levels to return to normal after eating).

- Consider a diet with moderate complex carbohydrate intake (rice, sweet potatoes, quinoa, whole wheat bread, etc.).

- “Carbohydrate tapering” (consider removing complex carbs late at night – One reason why carb tapering is a good idea is that insulin sensitivity (opposite of insulin resistance) decreases as the day goes on. This means your pan-creas must pump out more insulin for the same carbohydrate meal. Higher insulin levels contribute to fat storage).

- Limit stimulants late at night (coffee/energy drinks).

- Ditch the sugar-filled pastries, especially at night.

Exercise

- Experts say exercise adds seven years to your life; it doesn’t have to be fancy – consider a resistance program with cardiovascular work.

- Exercise helps the body improve insulin sensitivity.

- Do not “over train,” which leads to elevated cortisol levels.

- If you’re stuck behind a desk, or in your patrol car for extended periods of time, get creative — move your body.

- Find ways to de-stress.

Supplementation

- Magnesium, which as my colleague Scott Woodhall stated, “is the most underrated and effective supplement available. It can help the body in various ways including reducing stress and acting as a sleep aid. Avoid the “oxide” variety and use either “citrate or glycinate.” Woodhall recommends approximately 250 mg before bed and pointed out it is not toxic.

- Ashwagandha is an “adaptogen,” which is best known for its stress-lowering effects. The medicinal herb appears to help lower levels of cortisol. More specifically, daily doses of 125 mg to five grams for one to three months have shown to lower cortisol levels by 11 to 32 per cent.

- L-theanine is thought to work by decreasing “excitatory” brain chemicals that contribute to stress and anxiety while increasing brain chemicals that encourage a sense of calm. Also, non-toxic, it’s even been known to lower stress-related blood pressure and heart rate. Consider dosing 200-400 mg.

The bottom line here is controlling cortisol and preventing insulin resistance is crucial for police officers to main-tain healthy lives, both mentally and physiologically.

Making better nutritional choices, maintaining a regular exercise regime and considering supplementation can be extremely effective in preventing chronic disease and staying leaner. Looking to 2021, let’s support each other dur-ing these difficult times and make our health a priority — let’s be fit for duty.

Derek Thistle is a 14-year member with the Calgary Police Service. He’s a patrol sergeant and certified nutrition coach. For more information, visit www.tacticalnutritioncoach.com.

Print this page